The warehouse, manufacturing and distribution sectors operate in high labour and often heat intensive environments. This can lead to heat stress, which is proven to result in lost productivity through lowered cognitive functions, absenteeism and lowered physical capabilities.

What is Heat Stress?

Before delving into how to overcome heat stress, it’s important to understand what it is and how it can affect individuals and a business. The human body is constantly working to maintain an ideal temperature of around 36–37°Celsius. Heat stress occurs when the body is unable to cool itself enough to maintain a healthy body temperature. It relates to the total heat load on the body from all sources, including ambient air temperature, radiant heat, air movement, relative humidity, clothing and physical exertion.

3 Primary Forms of Heat Stress include...

- Heat Cramps - caused by performing hard physical labour in a hot environment. Symptoms include: muscle cramps; pain or spasms in the abdomen, arms or legs.

-

Heat exhaustion – a result of excessive loss of water and salt through sweating. It is extremely dangerous if the affected person is operating machinery. Symptoms include: rapid heartbeat and profuse sweating; extreme weakness or fatigue; dizziness or fainting; nausea or vomiting; elevated body temperature; headache; thirst.

-

Heat stroke – a medical emergency, heat stroke occurs when the body’s temperature regulating system fails and the body temperature rises to critical levels (greater than 40°Celsius)i. This can cause death or permanent disability. Symptoms include: high body temperature; confusion or loss of coordination; hot, dry skin or profuse sweating; throbbing headache; seizures; coma. Workers experiencing heat stroke may also stop sweating.

The Financial Impact of Heat Stress

A report published in the journal, Nature Climate Change, estimated the cost of work absenteeism and reductions in work performance caused by heat in Australia during 2013/14 was approximately $885 per person across a representative sample of 1726 employees. This amounts to an annual economic burden of approximately $8.3 billion for the Australian workforce.

From 2000 to 2019, there were 1,774 workers' compensation claims resulting from working in heat, and 441 of these were claims regarding heat stroke or heat stress.

The Health and Safety Impact of Heat Stress

As building operators and owners, we have an obligation to create a safe, comfortable indoor environment, especially in warehouses where thermal comfort is key to keeping workers safe and healthy. Exposure to heat has killed more people in Australia than the sum of all other natural hazards, according to a 2014 report published by the journal, Environmental Science & Policy. Worryingly, studies show workers routinely overestimate their heat tolerance, believing they are capable of continued work in high heat.

Put a worker in a hot warehouse and expect them to maintain high levels of activity?

You’re in trouble.

For every additional 1 degree celsius increase in temperature, you’ll lose another 2% in worker’s performance. Anything above 32 degrees celsius and heat-related illness risk increases and safety concerns increase and heat stress becomes a very real risk.

A New York Times article (July 15, 2021) reported new research that shows heat stress has led to an additional 20,000 workplace injuries each year in California alone. This is alarming when you consider how much harsher Australia’s climate can be in comparison. The data suggests heat increases the incidence of workplace injuries — such as falling, being struck by machinery or mishandling machinery — by making it harder to concentrate.

What the WHS laws say about Heat Stress

Australian Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) laws do not specify a ‘stop work’ temperature. However, WHS laws require any person conducting a business or undertaking (PCBU) to monitor temperatures in the workplace and eliminate or minimise the risks of working in heat. “The model Code of Practice: Managing the work environment and facilities recommends that work be carried out in an environment where the temperature range is comfortable for workers and suits the work they carry out.

How can we reduce the Risk? (Hint: Fans!)

Fans cool people, not rooms. They create airflow that quickly evaporates perspiration from the skin, carrying away heat. They also reduce the thickness of hot, humid air that builds up around workers. This improves heat dissipation and helps people’s natural cooling mechanisms to function more efficiently.

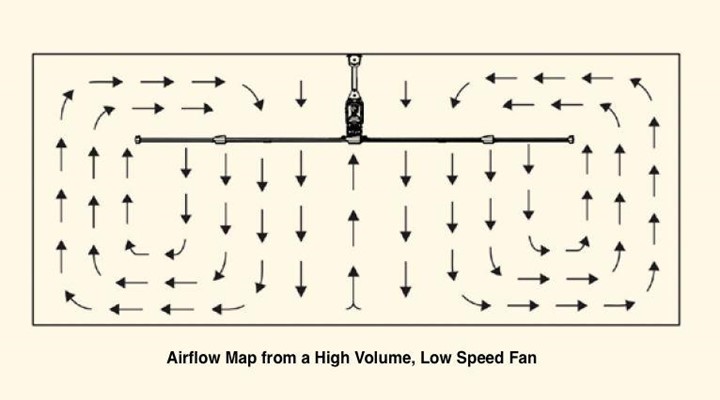

Elevated air speed and increased air circulation directly improve occupants’ thermal comfort. The air from a high volume, low-speed fan moves toward the floor in a column that radiates in all directions, flowing horizontally until it reaches a wall — or airflow from another fan — at which point it turns upward and flows back toward the fan. This creates convection-like air currents that build as the fan continues to spin. The increased air circulation accelerates the rate in which sweat can be evaporated from the skin. The result is a silent, non-disruptive and even distribution of 4.8- to 8-kph breezes over large spaces, with a perceived cooling effect on occupants of up to approximately 6°C.

Some Light Reading

We make a lot of claims about heat stress and Australian legislation. To see where we got our information from, see below.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heat-stroke/symptoms-causes/syc-20353581

Coates, L., Haynes, K., O’Brien, J., McAneney, J., Dimer de Oliveira, F. (2014) ‘Exploring 167 years of vulnerability: An examination of extreme heat events in Australia 1844–2010, Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 42, 33–44.

Hanna, L. (2017) ‘Coping with the Heat. Mismatch: Perceptions v Reality’, presented at the 15th World Congress on Public Health at Melbourne Convention Centre.

Flavelle, C. ‘Work Injuries Tied to Heat are Vastly Undercounted, Study Finds’, New York Times (July 17, 2021)

Staal, M.A. (2004) Stress, Cognition, and Human Performance: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework, Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California, 86¬-88.

Parsons, K. (2002) Human Thermal Environments: The Effects of Hot, Moderate, and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort and Permanence, CRC Press, London.

Zander, K., Botzen, W., Oppermann, E., Kjellstrom, T., Garnett, S. (2015) ‘Heat stress causes substantial labour productivity loss in Australia’, Nature Climate Change, 5, 647–651.

UNDP (2016) Climate change and labour: Impacts of heat in the workplace, with UNI-Global, ILO, ITUC, ACT Alliance, IOM, and WHO, New York: UNDP.

Safe Work Australia (2018) Model Code of Practice: Managing the work environment and facilities: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/model-code-practice-managing-work-environment-and-facilities

Taber, C., Colliver, D. (2018) Thermal Comfort in Heated-and-Ventilated-Only Warehouses, ASHRAE Journal.

Australian Institute of Health and Safety Report

-160x160-state_article-rel-cat.png)

-160x160-state_article-rel-cat.jpg)

-205x205.jpg)

-205x205.jpg)

-205x205.jpg)

-205x205.jpg)

-205x205.jpg)